What is Doughnut Economics?

Sustainable Business Leadership

As sustainability leaders continue to strive for environmental stability, income equality and social justice, traditional economic models have been under scrutiny for failing to adequately address the world’s most pressing challenges.

In response, a revolutionary concept known as ‘Doughnut Economics’ has been created which offers a fresh perspective on realistically balancing the needs of people with the limitations of our planet.

In this blog, we explore the doughnut economics model in more detail, assessing its seven key principles and the sustainable impact it can have on the world.

Learn more about our Sustainable Business Leadership courseThe definition of doughnut economics

Firstly, let’s begin by answering the question, ‘what is doughnut economics?’

The doughnut economics model was created by Oxford Economist, Kate Raworth in her book ‘Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist’, with the aim of creating a regenerative economy that’s beneficial and realistic.

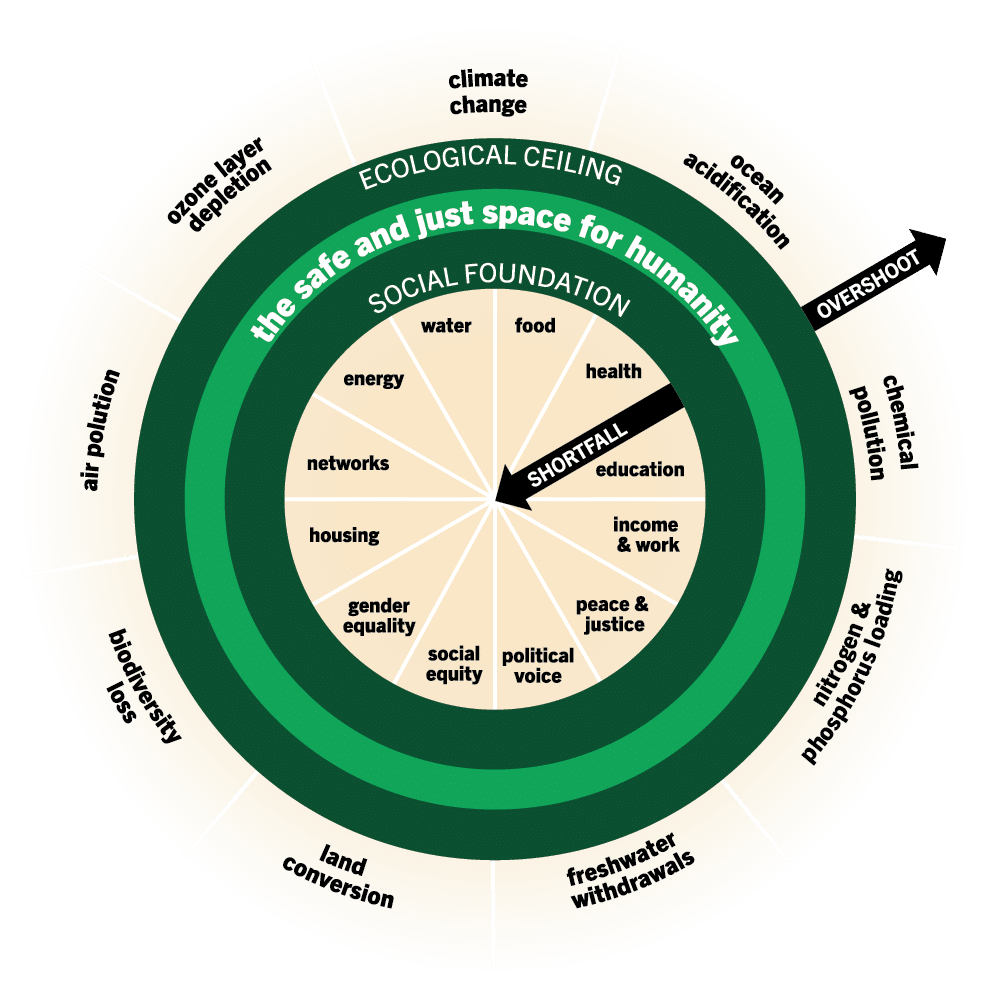

The sustainability model is split into three key areas:

- Social foundation

- The safe and just space for humanity

- Ecological ceiling

The inner ring of the doughnut represents the basic human needs that everyone requires, including water, food, health, education, income and work, peace and justice, political voice, social equity, gender equality, housing, networks, and energy.

The outer ring shows the boundaries which humanity must not exceed in order to remain sustainable. This includes elements such as climate change, ocean acidification, chemical pollution, nitrogen and phosphorus loading, freshwater withdrawals, land conservation, biodiversity loss, air pollution, and ozone layer depletion.

Its circular doughnut shape signifies the need to find balance between ‘social foundation’ and ‘ecological ceiling’ which is referred to as ‘the safe and just space for humanity’, where wellbeing is developed for both people and the planet.

Anything that falls outside of the doughnut as either a shortfall in the social foundation or overshoot in the ecological ceiling can prove catastrophic to humanity in the form of irreversible poverty or environmental damage, making balance important to maintain.

What are the 7 principles of doughnut economics?

Now we’ve explored the doughnut economics definition and its three key areas, it’s time to look a little closer at the 7 principles of doughnut economics. This offers a more robust approach of how the model can be lifted from an ideal framework to something that can be executed in reality.

1. Change the goal

The first principle highlights the need for humanity to shift the goal away from the relentless pursuit of economic growth measured as ‘GDP’, to one of meeting the needs of all within the means of the living planet. The goal should be the Doughnut, which represents the ‘safe and just space’ for humanity.

2. See the big picture

Principle two is about recognising that economies, societies, and the natural environment are interdependent systems. We need to take a step back and view the economy not as a self-contained system existing independently of the living world, but one that is embedded within society and the natural environment.

3. Nurture human nature

As the doughnut economics model places a ‘social foundation’ at the core of the inner ring, human values and needs are established as hugely important, rightly acknowledging them as a central focus to ensure that all of humanity can thrive.

4. Get savvy with systems

In another sustainable leadership blog, we highlighted how sustainability managers need decision-making skills to understand frameworks and solve issues. The fourth principle of doughnut economics proposes something similar. We must engage with doughnut economics to better understand different economic and environmental perspectives and make informed decisions.

5. Design to distribute

This principle recognises that inequality is a design failure and encourages us to design economies and societies to radically reduce inequalities. This means designing economies to be more distributive of value to those who help generate it and building a society which thrives on mutual benefit and accessibility for everyone.

6. Create to regenerate

Principle six is about harnessing the potential of regenerative design to reshape the harmful degenerative designs of past products and services into processes which give back. Through ‘create to regenerate’, new strategies that better support the planet can be developed and executed, with the goal of creating a circular, not linear, economy.

7. Be agnostic in terms of growth

The 7th and final principle of doughnut economics summarises the purpose of the model which is to shake off our addiction to economic growth, and strive for growth in forms greater than monetary output, such as sustainable progress, environmental benefits, and wellbeing for all.

“At this point in human history, the movement that best describes the progress we need is coming into dynamic balance, by moving into the Doughnut’s safe and just space, eliminating both its shortfall and overshoot at the same time.”

What are some doughnut economics examples?

Sustainability models such as doughnut economics help countries, people and businesses tackle some the world’s most pressing sustainability issues. Here are some examples of it in practice from three different countries.

1. Amsterdam, Netherlands

Amsterdam was the first city to use the doughnut economics model to target 100% reuse of raw materials by 2050. The approach was simple: set up projects within ecological boundaries that mutually benefits the cities interests both environmentally and economically.

These communities act as change agents and have rolled out several initiatives including the transformation of Fort Island Pampus, a UNESCO-world heritage attraction east of the city. The popular site is changing its entrance building, warehouse and ports to run on sustainable energy systems that eliminate existing fossil fuel usage. In addition, the island will benefit from reduced running costs in the long-term, whilst improving the ‘energy’ element of its social foundation.

2. Melbourne, Australia

Regen Melbourne was created in late 2020 as a platform to transition to a more regenerative city and move Greater Melbourne into the safe and just space of doughnut economics.

A key project of Regen Melbourne is to transform the Birrarung/Yarra River from a polluted river (caused by mass dumping and deforestation) to one that is swimmable by 2030. The initiative is divided into work streams including legal policy, river health, business and capital and swimming activations. All are required to help the project succeed.

It will help meet the social foundations of ‘water’ and ‘health’ and reduce the risk of ‘freshwater withdrawals’ and ‘biodiversity loss’ by restoring the river to its original state and protecting the region’s future water supply.

3. Leeds, United Kingdom

A little closer to home, Climate Action Leeds introduced the model to Leeds to transform it into ‘a city where people and planet thrive’. A detailed report found that various aspects of life in Leeds falls below the ‘social foundation’ and exceeds the ‘ecological ceiling’. So, by 2030, the group intend to create ‘a zero-carbon, nature-friendly, socially just city’.

Building engaged networks and well-connected communities is at the forefront of this challenge, so to bring people together, Imagine Leeds has been set up to offer monthly climate action events for local residents, businesses and stakeholders to come together. The principles of doughnut economics form the basis of these events, encouraging organisations to work in a regenerative and redistributive fashion to overcome the key issues facing the city.

Learn Contemporary Economics

Amongst other benefits, as part of our online Sustainable Business Leadership Masters/Postgraduate Certificate (PGCert), you’ll study sustainability theories and models like doughnut economics in more depth during the Contemporary Economics module which is just one of many taught on the course.

Here, you’ll learn about the relationship and associated complexities between economics and sustainability, considering this relationship from a variety of perspectives such as neoclassical, environmental and ecological economics. Drawing on this knowledge, you’ll have the opportunity to:

- Critically analyse established economic concepts.

- Appraise the complex interface between economics and the environment.

- Consider alternative economic approaches including environmental and ecological economics.

Study Sustainable Business Leadership online with the University of Leeds

Ready to enhance your knowledge and skills for a successful career in sustainability?

Our course teaches sustainability techniques, concepts, and analytical skills to help you solve complex business issues.

It’s a result of a collaboration between Leeds University Business School and the School of Earth and Environment at the University of Leeds. You’ll learn to develop sustainable business strategies, gaining the skills employers need, and ultimately supporting the transition to a more sustainable economy.

Did you enjoy this blog? Here’s some related sustainability content you may be interested in:

Want to learn more about our online Sustainable Business Leadership course?

Check out the course content and how to apply.